Helene Schjerfbeck, Robber at the Gate of Paradise, 1924–25

JULY 2020

Helene Schjerfbeck (1862–1946) wrote in a letter to her friend Einar Reuter in October 1924: “… I have begun to paint the back, a young peasant from a local farm has already sat twice for me. Oh, how beautiful, a strong muscular back – and it is so nice to pain something new.” The painting was created during the winter, before the artist moved from Hyvinkää to Tammisaari.

Schjerfbeck’s model was farm owner Alku Jaakkola, of whom people in Hyvinkää know an anecdote, as to how in his older years he referred to his first name which in Finnish means ‘beginning’ and introduced himself jokingly: ”I am the beginning and the end of Jaakkola” – the family had not been blessed with an offspring. The aim was to paint an image of the Christ. When the work progresses the artist, however, started to see her model in a new light: ”I noticed that he resembles a young satyr.” The image changed at the same time transforming its ambiance. The initial gloriole around the head became dimmed down into a ring of shadows which is melting into the dark backdrop, the closed gate of paradise. The work had become human and secular and the Christ converted into robber.

In its time of completion, Robber at the Gate of Paradise was an exceptional portrayal of man. It was created by a female artist who had attained the age 62. Throughout the art history, it had been customary to see sensual female models as an object of male painters’ gaze. An opposite proposition was unheard-of in Finland in 1920s. Schjerfbeck is viewing her object, a full-blooded male model, and admiring his bodily beauty. You cannot find any signs of shyness or maternal instincts in the picture. A strong emotional charge has been created with intense colours and intensive form handling in which the contours are faded out with colour. It is related to the modernists, to Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Kees van Dongen, whose output the artist studied by means of the art magazines she subscribed at the time.

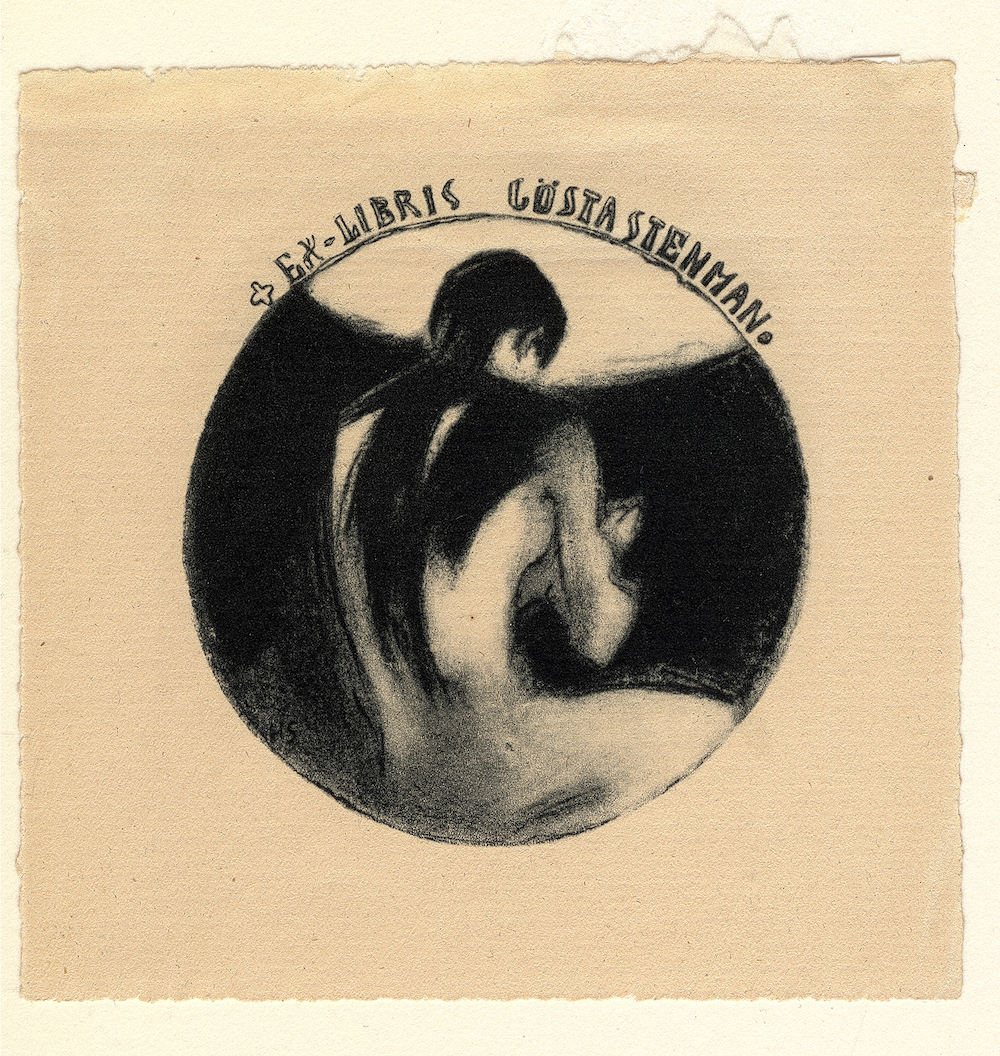

Helene Schjerfbeck intentionally left her Robber painting unfinished because she suspected that a second retouching would have impaired the effect. The painting was exhibited for the first time as late as mid 1940s. The public was probably not ready to embrace the work at time of its completion. A supporter and promotor of Schjerfbeck’s career, art dealer Gösta Stenman knew of the work even though his salon never exhibited the work. The motif of the painting Robber is one of the three ex-libris motifs which Stenman commissioned of Schjerfbeck.

Although physically distressing, the artist’s move from Hyvinkää to Tammisaari in summer 1925 however brightened up her spirit. She had prepared for it for months. Large-sized Robber at the Gate of Paradise which did not find a place among artist’s moving goods, was left in Hyvinkää in the hands of a good-hearted doctor Erkki Calonius. After Schjerfbeck’s mother had died doctor Calonius har offered the artist a smaller apartment in which she had resided her last months in Hyvinkää. Calonius had offered to help the artist by finding models and dealing her paintings to his clientele. Along the way, he could increase his own art collection. The work Robber at the Gate of Paradise was passed as a family heritage in the Calonius family until early 21st century. The work once changed owners via an auction house in London before it ended up to the Gösta Serlachius Fine Arts Foundation’s collection in 2015.

Tarja Talvitie

Head of Collections