Mänttä Castle – A Dream Unfulfilled

DECEMBER 2021

One of the most intriguing buildings in the history of Mänttä is the Mänttä Castle. Located near the paper mill on Mäntänkoski rapids, it used to be the family residence of Gustaf Adolf Serlachius who initiated the industrialisation of Mänttä in 1868. The architectural drawings of the castle are comprised in the drawings collection of the Serlachius Museums.

Gustaf Adolf along with his family resided their first decades in Mänttä on the brink of the Mäntänkoski Rapids in the so-called Mill cottage, a wooden building resembling a main building of a farm. Finally, early 1890s it was time to create a presentable home, appropriate for his position. G. A. Serlachius commissioned the plans of Swedish architect A. E. Melander.

Dated in January 1891, Melander’s design for Serlachius residence represented in its time fashionable Neogothic style. The brick façades were ramblingly unsymmetrical with their protrusions, narrow towers and pointed battlements. The decorative masonry of the triangle roof constructions and narrow windows reminded one of Medieval town houses.

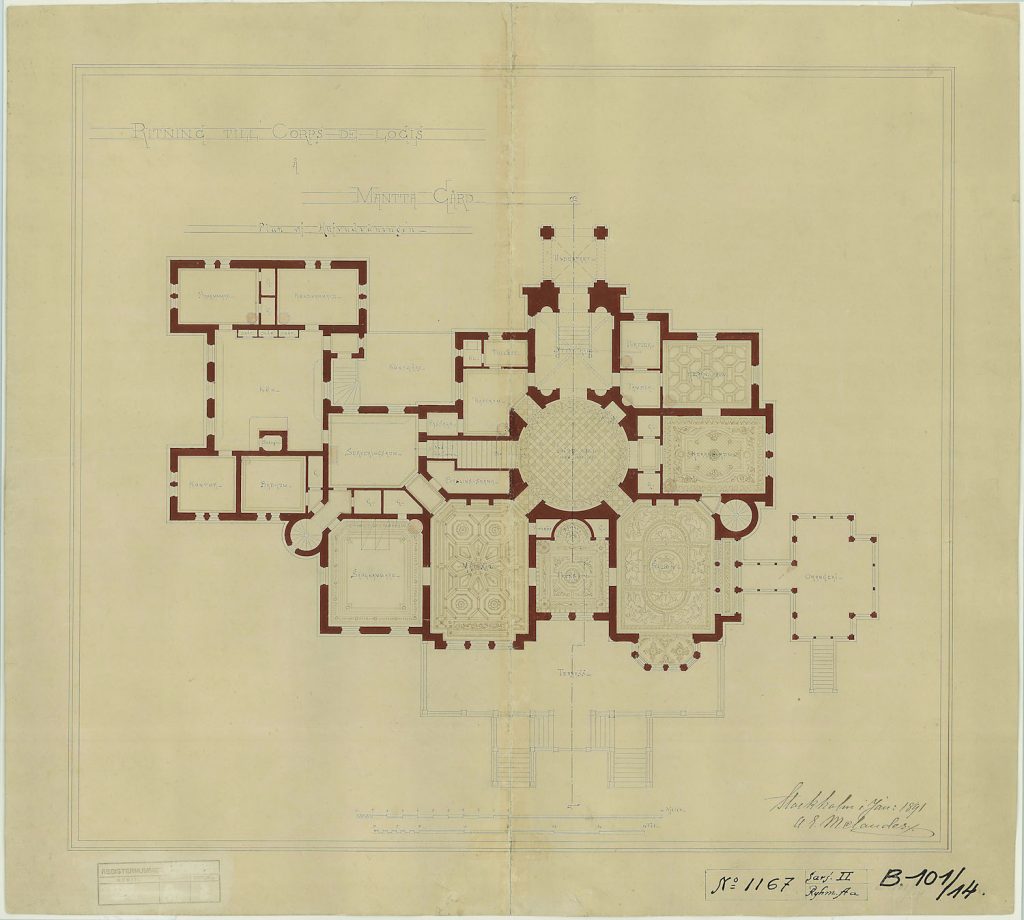

The floor plan designs reflect the ways of bourgeois household. The residence of the mill owner had been designed to meet the needs of the family, servants, and guests. Much like people, the rooms had their own hierarchy which was displayed in their location, size, and interior design. The floor plan included drawings of the ceiling decorations of the most important rooms, which allows one to deduct what kind of style was regarded appropriate for each space. Downstairs, the most formal spaces were the two-floor tall central hall, downstairs salon, and dining room. Between the two latter falls one slightly smaller but ornamented room for the lady of the house. The salon had large windows, oriel, and an access to the conservatory. Rooms for the porter and cloakroom were located near the main entrance, and in the corner, there was the smaller master’s room. In between it and the salon lied a larger master’s room on the end wall. The master and lady’s rooms were not bedrooms, but there was a specific one between the dining room and the maintenance wing. A bathroom was situated close to the bedroom.

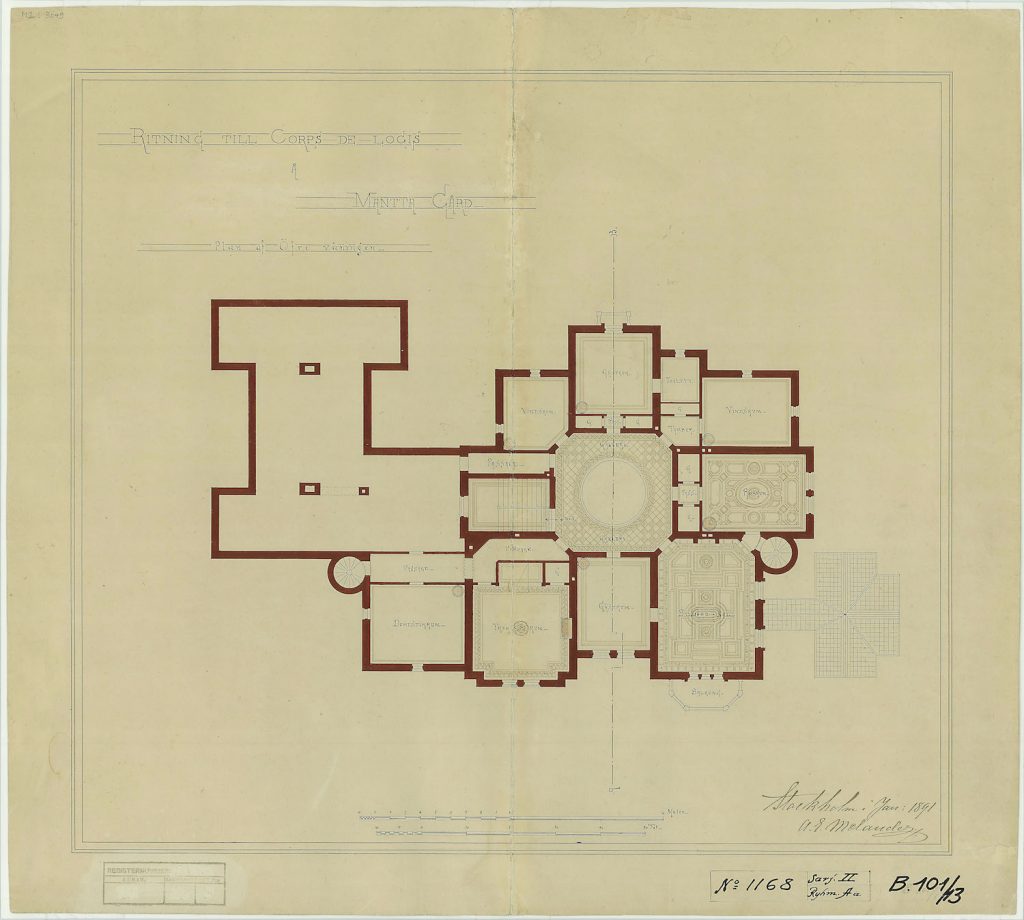

Two guest bedrooms, Ms Serlachius’ bedroom, tobacco, and billiard rooms as well as two attic rooms, apparently meant for storage spaces, were located on the first floor. The staircase was in the open central hall which on the first floor converted itself into a gallery. The two round towers designed for the building had spiral stairs, one of which offered a direct connection from master’s room to the billiard parlour and tobacco room, the others were utilized by the servants.

The lower end of the building was reserved for the servants. Entry was on the same side with the parade entrance but shielded by the kitchen garden separated by a wooden fence. Kitchen, office and two small bedrooms were on the ground floor. On the first floor near the spiral stairs there was a larger servant’s bedroom which was conveniently close to their hosts both upstairs and downstairs. The servant facilities were linked with the gentle folk’s side through narrow corridors and service room. The building was full of closets and small connecting passages between spaces, and it had several rooms in the basement.

In the end, only the most festive spaces of Melander’s design were realised on the end of the house: three rooms on the ground floor and three on the first floor. Servants side and most of the gentle folk’s premises were substituted by connecting the old Mill cottage as a part of the new residence. Despite that, the building, which for a good reason was named as castle, constituted a surreal sight between the workers lodgings and the mill.

Where had the idea for a Neogothic exterior come from? According to a legend, its paragon was a printed image acquired in Paris. Timber trader Sörensen’s country-side residence, which was designed by Melander in Torreby in Sweden (1887), was quite much alike. On the other hand, the Mänttä Castle has been paralleled for example with Timrå-located Merlo Castle (1883–1885), which belonged to Fredrik Bünsow, in his time Sweden’s wealthiest forest industrialist. Unlike the Mänttä Castle, those castles are still standing. The isthmus between two lakes started to fill up as the in the 1910s established pulp mill was expanded, and the castle was demolished in 1939.

Milla Sinivuori Hakanen

Senior Curator

Sources and further information:

Serlachius Museums’ Photograph and Drawings collections.

Karl Emil Lindblad Archival Collection, Serlachius Museums.

Keskisarja Teemu, Vihreän kullan kirous (Curse of the Green Gold), 2010.

Serlachius Museums’ Pearl of the month January 2016: https://serlachius.fi/en/mantta-castles-fountain-sculpture/

Serlachius Museums’ online publication Mänttä evolves: https://serlachius.fi/en/museums-and-collections/online-publications/mantta-evolves/

Ahnlund Mats and Brunnström Lasse, Bolagssamhällen i Norden – från brukstid till nutid, 1993:

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1533416/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Merlo archive https://www.sca.com/sv/om-oss/Detta-ar-sca/vara-verksamheter/merlo-slott

Torreby castle https://festningshotellene.no/torreby-slott/sv/slottet/