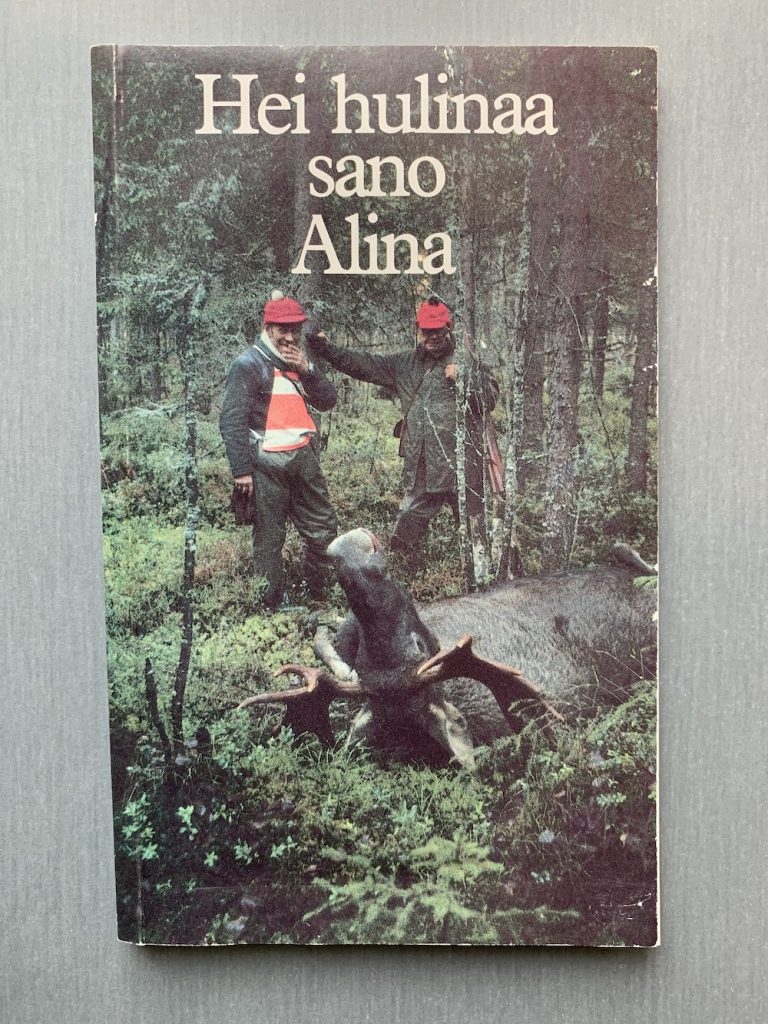

Hei hulinaa sano Alina – Anecdotes of the Hunting Club gents and impressions from the mill-owner era

OCTOBER 2020

An extraordinary piece of literature in Located in Serlachius Museums’ library, Hei hulinaa sano Alina (Come on, let’s hustle up now) tells the stories about Mänttä Hunting Association. In 1987, Jouko Kuukka compiled it in the purpose of “saving memories connected to hunting and people involved in that hobby” conscientiously based on the facts. The book was named after an expression that R. Erik Serlachius, one of the key persons in the club’s history, used in order to raise the moods during a get-together after a hunt.

Mänttä Hunting Association was established in Gösta Serlachius’ era in 1930. In the realm of G. A. Serlachius Ltd, it was one of the associations that emerged in order to tether the high-ranking officials to the company. Among the male residents of Mänttä as members were hand-picked such persons who were considered suitable and majority of whom either worked for the Serlachius company or had otherwise a pivotal position from company’s perspective. Hunting Association was a kind of a club of gents where the central figure in its operations was patriarchal mill owner Serlachius, who were industrialists in three generations. During the time of the third and last mill owner, Gustaf Serlachius, when the G. A. Serlachius Company paved way for Metsä-Serla in 1987, stories and anecdotes from the beginning of the association were still vivid in the memory of its members.

In addition to hunting, Hei hulinaa sano Alina describes the working culture, image of “a right kind” of a man and ways of communication in the era of the patriarchal mill owners. According to Kuukka, all members of Mänttä Hunting Association were equal. The built-in hierarchy of the mill society is however clearly visible in the form of address and code of conduct which is signaled in the stories. They reveal that recruitment both to work and Hunting Association was based on personal preferences and relations. A person hired by the Serlachius Company was expected to participate in free-time activities of his or her own level. Men were expected to be honest and able to hold their liquor when alcohol was offered. Particular attention was directed to the way a person provided feedback. Several stories witness how, in appropriate occasions, persons were educated by being zapped or humiliated for doing something in a wrong way. Based on the set of the anecdotes, it is impossible to say, weather the inability to communicate abided by the spirit of the time or weather the less dramatic ways of action were left out because of their mundane nature.

Serlachius family’s circle of acquaintances and, along with that, the hunting companies comprised influential men from business life and politics all the way to Finnish president. Subsequently, the hunting memories include anecdotes from the national level. One of them is connected to politician and Minister Ahti Karjalainen: Swedish King Carl XIV’s visit in Finland in 1975 included a pheasant hunt in Mänttä. In Finnish, pheasant is called fasaani. When a magpie flew by, the king asked Finnish President Kekkonen in Swedish “Vad är det för fågel?” (What bird was that?) Kekkonen could not make out the question and asked “Va sa Ni?”. Ahti Karjalainen who accompanied them shot immediately and hit the bird.

The previous anecdote describes aptly how anecdote is generated as well as its close link to its own time. In its core are Minister Karjalainen’s allegedly poor knowledge of languages, particularly his awkward sounding pronunciation of English language as well as a magpie that could be found in the media coverage which instead of Mänttä dealt with the royal pheasant catch in Janakkala. Ahti Karjalainen did not participate in hunting party in Mänttä nor was he a known as a hunter either, unlike the Swedish king who probably would not be misled by a magpie. “The story contained no truth whatsoever”, as Kuukka states in his book. It was a funny story, however, and typical for such funny stories, it happened to someone we know. Even though the anecdote does not open up to later generations without additional explanations, it condenses several stories of its time. Perhaps the same goes for the compilation Hei hulinaa sano Alina.

What is the story behind the book? Mänttä’s last patriarchal mill owner Gustaf Serlachius had supported the compilation of memories into Mänttä Hunting Association’s chronicle; without his blessing it would hardly have been collected, anyway. When he heard about its print run of thousand issues, without reading the book he stated firmly that only five issues were needed: one each for the author, editor, proof-reader and himself as well as one for the archives, “others will be destroyed by burning!” Maybe Gustaf Serlachius felt uncomfortable revealing the stories of the inner circle. Fortunately, forester Häggman kept a pile of books on his attic. This is the reason why the book is stored also in the library of the Serlachius Museums.

Milla Sinivuori-Hakanen

Curator

Sources:

Kuukka, Jouko 1987. Hei hulinaa sano Alina. Mäntän metsästysyhdistys ry. (Mänttä Hunting Association), Mänttä. Collection of oral history on hunting 2008–2009, Serlachius Museums, Archive of oral history.