Simon Patterson: I am interested in history painting

The British artist Simon Patterson was born in England in 1967. He finished his studies at Goldsmiths College in London 1989 and had his first solo exhibition in Glasgow, Scotland the same year. Patterson has exhibited widely in in museums and galleries in Europe, Japan and United States. He had a solo show in Helsinki in 1994 and in 2014 he took part in SuperPop!, the opening exhibition of Gösta’s new pavilion.

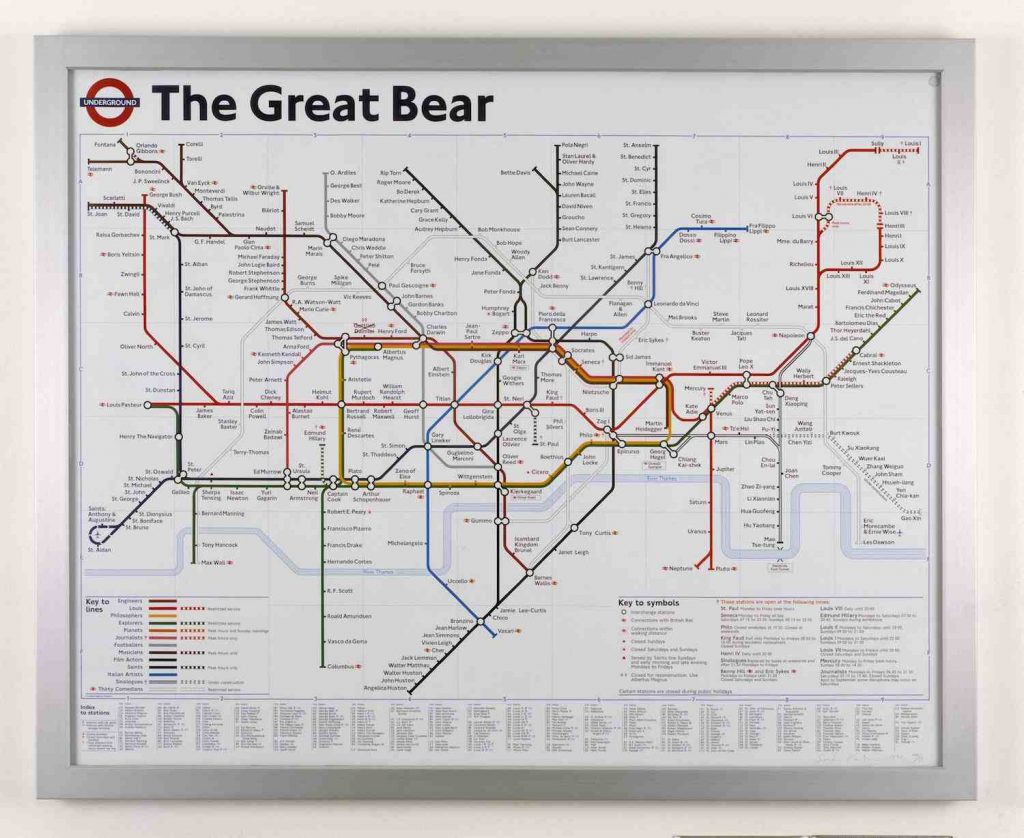

Patterson’s work escapes easy definitions, but perhaps one could call him a conceptual pop artist. Often, he bases his works on common maps, diagrams, lists and manuals, things we use while trying to structure the world around us. His perceptive works direct us to think about what and how we know of the world we live in. The elements he uses are thoroughly familiar. It is their unexpected combinations that show the world in a new light.

Simon, what triggers a new work?

I can retrospectively recognise various triggers. One starting point is to make works for a small imagined audience, chamber works if you like. In Mikrokosmos, 2019, I was trying to make something small in scale but large in scope. It ostensibly comprises a fake stamp album of European nations. I was attempting to replicate the personal and singular intimacy you have when reading a book or perusing a small museum artefact in a vitrine. The trigger here was not the subject or the form, but the means of receiving the work however nebulous that may seem.

There is no one single process to the finished work. In some instances, ideas come about almost perfectly formed, but this is rare. Usually, there is too much material, and I have to edit the idea down by lopping-off ideas or actual components. On other occasions I have a visual idea which is just an empty vessel waiting to be filled. Sometimes, you realise that the idea has been partly handed to you by something that you have read or seen or exchanged via a conversation.

You use a wide range of materials and techniques. How do you choose the visual and the material form of each work?

This is the most crucial part of any work. I always hope that I have chosen the right medium for the idea. It is equivalent to starting to paint something before choosing the size or format of canvas. The more I develop the idea, the more it becomes obvious to me what medium is best suited to it.

When is a work ready?

Completing a work is only difficult if I have not established the rules or parameters for making it in the first place. Usually these have already been partly determined by external forces like time constraints and limited budgets. An exhibition deadline certainly focuses the mind wonderfully.

What is the most difficult part of your working process?

Beginning a work. I admire the work ethic of artists like Andy Warhol and the studied dilettantism of Marcel Duchamp. I do not have a routine where I go to the studio and work in the way a painter might do – I generally find something else to do or read that is seemingly unrelated to the job in hand. That way, making something is work. It is a way of trying to distract myself from worrying about making art. If you treat it as work, then the art bit will take care of itself.

I never find joy immediately after the completion of a work, all I can see is the faults. This reminds me of Peter Fischli and David Weiss and their marvellous work ‘Suddenly this overview’, 1981, a set of hand-made unfired clay figures. The one that specifically comes to mind is that of two small figures with long hair and a guitar case trudging along a street presumably at night entitled: ‘Mick Jagger and Brian Jones going home satisfied after composing “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction”’. Catharsis, if it comes, never occurs when you most need it.

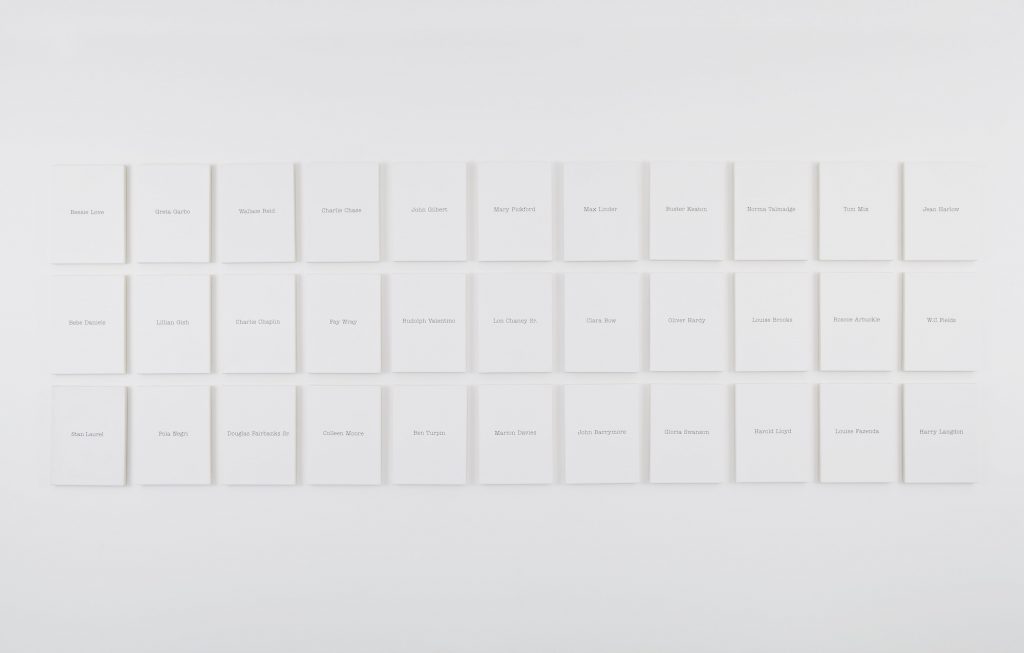

Words, especially names, are central to your work, film stars, presidents, scientists and so on, some well-known, some obscure. How do you choose them?

When I started making the name paintings back in 1987, the first work of this open-ended series was Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor. Their names alone conjured up in the mind’s eye not only what they looked like, but their films, private life and stardom. There aren’t many people who are that famous.

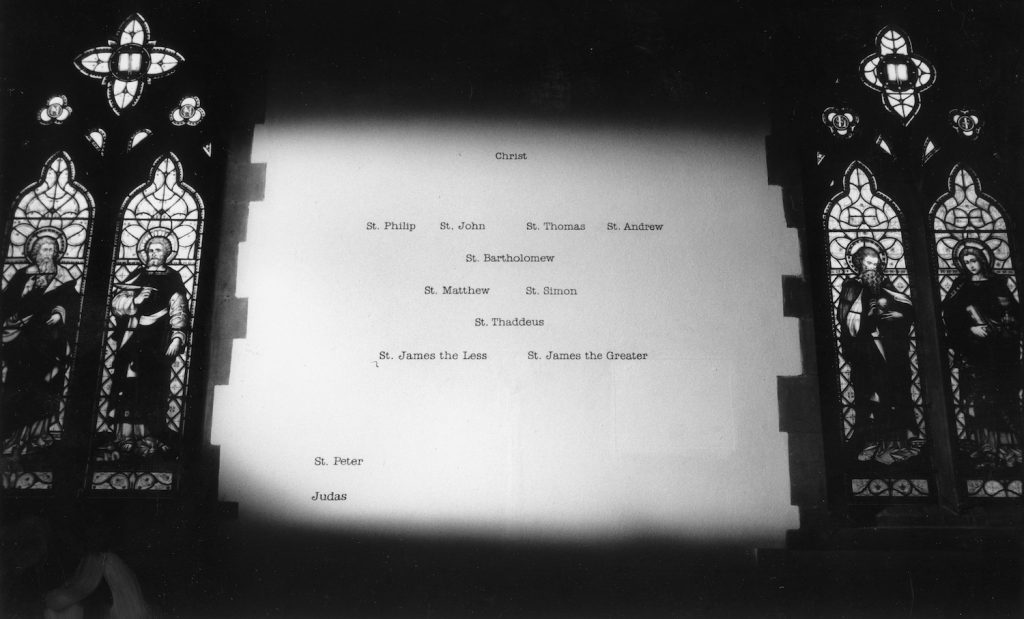

I realised subsequently, that, although the works were Pop in the guise of conceptual art, I was more interested in history painting. The Apollo 11 astronauts as a historical triptych: whereas you might not recall the faces of individuals, only perhaps a fuzzy black and white loop of Neil Armstrong descending the ladder of the Lunar module, the paintings were stand-ins.

From here, the content began to shift from remembered events to a wider history. I started to collect names and type long lists. Sometimes names were included purely for their musicality or their associations, sometimes as notional hooks to hang ideas on as part of map, grid or diagram. As there was no internet back then I played with other taxonomies – encyclopaedias, guidebooks, directories.

Many of your works refer to flying and tricks and stunts…

Flight or voyaging or even the idea of a safari are recurrent themes in my work. Sometimes, as is the case with the Valentina Tereshkova/Yuri Gagarin, the work is both a space age portrait diptych, a self-parody of earlier works such as the Burton/Taylor diptych, but also a commemoration and celebration of the heroic – however unfashionable that may be today.

Doubling or mirroring has long been a thread through my work. Standing in for someone or something else hugely appeals to me in terms of illusion. This inevitably leads on to works about magic and escapology. Flight as escape keeps cropping up in my work.

Ultimately, the names Yuri Gagarin or Jacques Yves Cousteau act as surrogates or alter egos for me.

Interview by Timo Valjakka, Curator of the exhibition