In a boat across the river of death

MARCH 2017

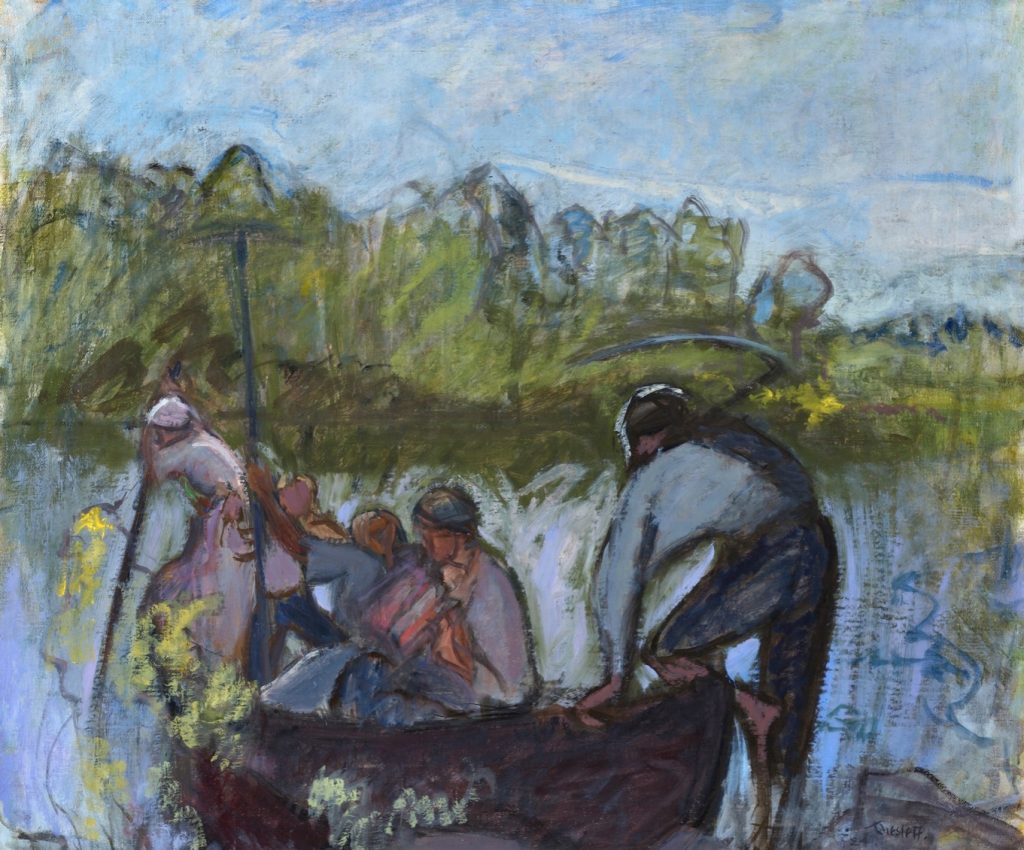

Man’s connection to nature is one of the cornerstones of Ellen Thesleff’s art. This reveals itself best in the paintings she painted at her summerhouse in Ruovesi. The water element and the journey by boat with its symbolism are intertwined in an especially impressive way in the large scaled painting Harvesters in Boat II from 1924. The work was acquired to the collection of the Gösta Serlachius Fine Arts Foundation in 2016.

The basis of the work of the painter and graphic artist Ellen Thesleff (1869–1954) was earth, water, fire and air. The further her artistic path led her, the more immaterial her visualizations became, and the higher was the level from which she looked into the world of ideas. The realism in the production of her youth has been characterized as a down-to-earth kind of ambiance lyricism, but at the beginning of the 20th century, the colourism of her paintings changed, which made Thesleff one of the most interesting forerunners of Finnish modernism.

Ellen Thesleff has in different contexts been called a symbolist, an expressionist, even an impressionist. In fact her art escapes all definitions of style. During her long career, she even consciously avoided theories and manifests. Her roaming the great art centres of Europe made her an early, international modernist. Especially Italy became a spiritual homeland for Thesleff.

In summer, however, the artist preferred to be in her home country, in the lake landscapes of Murole in Ruovesi, where also the painting Harvesters in a Boat II was created. The painting breathes a sense of hazy summer evening, but Thesleff’s works seldom lend themselves to being unambiguously explained. Quietly, and exhausted after the long day’s work, the harvesters are about to board the boat waiting in the shallow waters at the shore. The individual traits of the characters have vanished, as well as the lakeshore landscape, which seems to be teeming with hidden images of the spirits and wild animals of the folk tales.

In the foreground of the painting, the boat is being pushed into the water by a reaper, on whose shoulder a scythe is resting as a hardly observable detail. He is one of the working people returning from the harvest, but the duskiness of the evening and the unsharpness of the outlines mislead the viewer; perhaps what we actually see is the Reaper, the boatsman of the underworld, whose task it is to take the silent figures across the river of death. The death symbolism of the painting becomes clearer when you compare it to the woodcuts Boat Ride and The Grim Reaper from the same period. The nearness of death in the painting isn’t scaring – the way it is in her graphics – but mysterious.

The harvest, which marks the end of the growing season, prepares nature for winter and death, so that when spring arrives vegetation is revivified and reborn, and in this way the cycle of life continues from year to year. The painting can bee seen as a pantheistic statement on the part of Ellen Thesleff of the argument of human immortality, our eternal existence as part of nature. To her friend Gordon Craig, she wrote in 1920: “To me, life is a drama without beginning or end. How could there be an end?” The artist’s task is to strive for the beauty of nature, to melt into the endless cycle of nature.

“I’m pressing myself into the sand as deep as the depth of my heart, in order to hear the heartbeat of the earth, and at the pace of these beats I’m grabbing my colours, sure of myself and free”, Ellen Thesleff wrote after becoming conscious of the wonder of colours at the beginning of the 20th century. Over the years, her paintings became more and more airy, the rigid form softened. At the end, in the last paintings of the 80-year-old artist, we sense only the fireworks of colours. At this point, she summarized her message: “Truth and beauty are one. Absolute beauty exists: it’s at such a height that truth can never reach it.”

Tarja Talvitie

Head of Collections